Local Literati and Landscape Change, Part 2.

“This neighborhood of ours holds about a hundred and twenty-five acres… Within this area it has something of the diversity of a macrocosm. A part of our neighborhood, the greater part, is wooded hills, long-lying, gently rounded hills, the tipmost top of the highest part being a thousand feet or so above sea level. There is plenty of acreage of hemlock-dense woodedness to afford good sheltering place for white-tailed deer and good prowling place sometimes for a bobcat neighbor. Then the hills, as they slope downward, change from woodedness to sunny, open uplands and then change again to forty acres of bottom-land through which about a half-mile of brook runs crookedly. It was all a farmstead once upon a time, but not in many years…”

– Alan Devoe and Mary Berry Devoe, Our Animal Neighbors, pp. 2-3.

Shortly after John Cowper Powys (he of our 27 April 2011 blog) moved out of Phudd Bottom in 1934, Alan and Mary Devoe moved in. Later, they moved to the house on Hickory Hill Road which is now owned by the Dufaults. They lived there until Alan Devoe’s death in 1955. Although relatively little read today, Devoe’s books were an important contribution to mid-20th century American naturalist writing. His works often explicitly juxtaposed peace and death in nature with the contemporary tragedy of WWII. While some of his essays described Northeast wildlife with little reference to place, some of his books however, most notably Phudd Hill (1937; written at Phudd Bottom) and Our Animal Neighbors (1953; written at the Hickory Hill Rd house) provide specific snapshots of life on and around Phudd Hill during that era. John Cowper Powys and Arthur Davison Ficke (a local poet, see earlier blog) provided flattering fly-leaf snippets for Phudd Hill.

[Update Dec 2015: In October of 2015, former Hillsdale Town Historian Jay Rohrlich published a front-page article about Alan Devoe in the Columbia Paper; this interesting article, aside from providing excerpts of Devoe’s writing, places him in the context of preceding and contemporary nature writers.)

ACT I: Maps & Figures (and a couple of photos)

(WARNING: There now follow a series of maps and tables, but there is a set of forest photos after these… please bear with me, just trying to set the stage.)

Devoe’s writings, like Powys’, give a us chance to ‘taste’ landscape change. In Devoe’s time, Phudd Hill and much of the County was reforesting after a wave of agricultural abandonment in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

By 1950, “improved farmland” (a census term generally connoting worked, open farmland) in Columbia County was only half of what it had been at the peak of agriculture some 70 years before. Today, we have about one third of the peak farmland. Devoe’s landscape was largely one of young forests, shrubland and old field. We can illustrate the extent of that evolution by looking more closely at landscape change on Phudd Hill.

Percent of Columbia County in “Improved” Farmland (yellow); in Forest (green line); and as Shrubland (brown line).

This map, with Hawthorne Valley Farm represented by the red circle in the middle, illustrates how forest extent has changed over time in and around Hawthorne Valley. The purplish shading indicates the approximate extent of forest in the late 1920s; it is based on the forest delimitation indicated on a topo map of Kinderhook published in 1933 (and available on-line). The green shading indicates more or less the modern extent of forest based on the most recent topo map of the region. Notice how forest has expanded out from its early 20th century cores. Click on image to enlarge it.

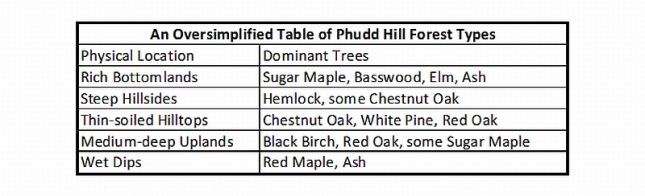

At the simplest level, one can perhaps say that the composition of a given forest is determined by two main factors: the physical setting (that is, soils, climate, exposure, topography) and history. Considering the limitations or opportunities provided by physical setting, one can perhaps say that Phudd Hill harbors five types of forest niches: rich bottomlands; steep, thin-soiled hillsides; level uplands on medium deep soils; dry, rocky hilltops; and moist, perched pockets. These locales grade into each other, and do share some tree species, but, at the same time, their dominant species are largely distinct. The table and mas below start to paint part (and only part) of the picture.

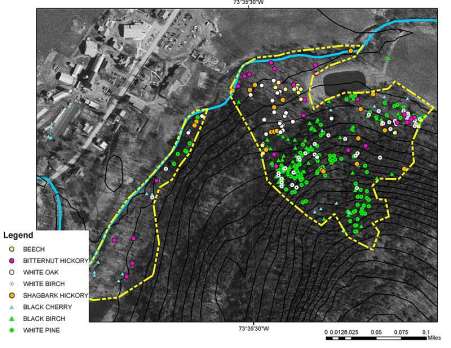

These are tree maps we made several years ago from the north end of Phudd Hill; this is the opposite end from the Devoe house, but the general distribution of tree types is similar. The black lines are topo lines climbing to the top of Phudd Hill which is just out of the lower righthand corner of the image. The dotted yellow line illustrates the extent of our tree surveys. The trees pictured here are primarily the trees of the moistest portions of the hill – the floodplains along the creek and the small-scale hillside valleys. (Click on image to enlarge.)

Red Oak and Sugar Maple are two of the most common trees on Phudd Hill, yet they have relatively little ecological overlap – Sugar Maple likes the richer soils (notice how its distribution somewhat follows those of the trees pictured in the previous map), while Red Oak searches out drier land. White Pine is scattered in these plots, which included no old, upland fields. (Click on image to enlarge.)

Here are the thin-soil, steep-slope specialists: Chestnut Oak and Hemlock. Chestnut Oak especially seems to be most common on the rocky hillsides, while Hemlock spreads a bit further onto flattish terrain, although it does not enter the wetter spots that Red Maple accommodates. Red Maple has one of the largest ecological ranges of any of our trees – from wet pools to dry hillsides. (Click on image to enlarge.)

These are the odds ‘n ends in some ways, but notice how even amongst these rare trees ecological partitioning is apparent. Bitternut Hickory, White Oak and Beech tend to stay on the deeper, flatter soils. Most of the other species seem to range more broadly. Black Birch’s distribution is interesting to note – I consider it a ‘middle of the road’ (or, rather, hill) tree: it tends to be found on neither the deepest, moistest soils nor the driest sections. Sorry about the White Pine repeat – it seems just as widely scattered as in the first map! (Click on image to enlarge.)

These maps illustrate how physical location can effect tree distribution. For the most part, the hillside shown above has experienced very limited clearing (albeit there is evidence of historical, perhaps woodland, grazing). However, to a large degree, the determinant of forests in our region is land use history. The age of the forest not only determines tree size, but also which tree species are present – some trees grow best in open sunlight and die out as they are shaded out by their elders; some trees grow best in shade and gradually take the place of the early colonizers. Furthermore, how a field was used and abandoned can also affect subsequent forest development. A pasture which was gradually abandoned over several years sports a different initial forest cover from a ploughed field which was abruptly abandoned. (Those of you who enjoy exploring forest history ‘on the hoof’ will like Tom Wessel’s book entitled, Forest Forensics.)

If this field were to be abandoned at this point, it seems likely that the White Pine towering in the background and beginning to sprout in the foreground would become dominant (photographed in Canaan).

This Hawthorne Valley pasture, on the other hand, is now dominated by the pokey likes of Red Cedar, Common Juniper, and Multiflora Rose. The first can develop into a low forest tree. The Rose clumps can go on to become nursery sites for other tree species which grow up within the sheltering thorns.

ACT II: Forest Photos (and a trio of maps)

On Thanksgiving Day and the following, we walked along the hill behind the former Devoe and current Dufault house. Both landscape position and landscape history influenced the forests we walked through. At the risk of scaring the reader off with more maps, I present three more – these are aerial photographs of the same patch of land: the hill behind the house. The first image provides one with an idea of the ‘lay of the land’ – one can look at this and, based on the earlier tree distribution maps, make some guesses about what trees would naturally occur where.

The last two aerials illustrate our walk. The first labelled picture is from 1952, the second from 2010. I have indicated on both maps the location of some of the photos we took during our walks. At each photograph site, I’ll try to briefly describe which trees were present and, in a crude way, make some guesses as to why those particular species were around. Interspersed with my verbal and locomotory ramblings are extracts from Devoe’s writing. Even if I’m not 100% sure of the location he was referring to, they give you another way of seeing the landscape he was living in.

This is a dense topo-line diagram of the southern end of Phudd Hill, the Devoe/Dufault house is indicated by the purple star.

Our walk overlaid on the 1952 aerial of the same portion of South Phudd. Those black dots invading the fields are predominantly White Pine.

The same area in 2010. Notice how fields that were just speckled with Pines are now Pine forests. Below, we show photos of those forests and some of the other sylvan new arrivals. The labels are in the same locations on each photo and so can serve as landmarks helping you compare the photos. You might want to open up another copy of this blog in a second tab so that, as we go through the following photos, you can quickly refer back to these maps.

“It will be best, perhaps, to explore first the hedgerows and thicketed places. These low-growing tangles are the favored sites of many birds, affording thick-foliaged shelter from sun and rain and being not readily penetrable by enemies. So set forth and investigate the old quince hedges that grow along tumble-down stone walls; look into the hawthorn bushes that dot old hillside pastures; see what the brambly patches of wild blackberry may hold. In a close-growing thicket of young maple saplings you may find, with luck, a wood thrush nest in progress…Investigate meadowsweet and smoke bushes; have a look into the tangles of wild grape.You may often find the nest of field sparrows in the meadow sweet, or in the smoke bush you may come across a vesper sparrow’s home…In the wild grape, or in a thorny jungle of blackberry, you may discover nests of catbird and brown thrasher, song sparrow and Maryland yellow throat… There is not space to mention all the nests which, by a little perseverance, you can find in the spring in bushes and low-growing thickets.Certainly you will find the cup, lined with horse-hair, which the chipping sparrow builds; you may find the stick nest of a shrike, felted over with bark strips and mosses; you will almost surely find a bluejay’s nest, built a little higher than your head and made coarsely and bulkily like a crow’s.”

– Alan Devoe, Down to Earth, pp. 122-125.

Photo Location A: This small field was apparently one of the last to return to forest, perhaps in the 1970s. This is not surprising given its proximity to house and barn. Relative to most of the other spots that we visited, the land here is flatter and the soil probably deeper. Its topography and vegetation suggested that it went from cultivated field to forest. It is now dominated by Sugar Maple saplings.

In case you’re uncertain of your winter tree identification, just look down. Sugar Maple leaves make up much of the leaf litter. Some care needs to be taken in deriving forest composition from leaf litter composition – Sugar Maple leaves, for example, decompose much quicker than oak leaves.

This is the wall that separates the B field (to the left) from the A field. Notice how the older trees along the wall tend to have the most branches on the right side of their trunk; this imbalance suggests that, when they grew up, the field to the right was still open while the field to their left was already growing up in woodland.

Photo Location B: As we walked up the ravine’s east side, we entered what used to be the west end of a larger field. In 1952, this appeared to be clean land, but by the late 1950s extensive invasion of woody plants is evident.

The same wall but now focussing on the terrain of the B field. Notice how there appears to be a ridge running parallel to the wall (most evident at the base of the large tree). This may be the remains of a plow terrace of sorts – farmers ploughed from hill top to hill bottom, folding the soil downhill as they went. When they reached the bottom, the mound beside the last furrow was left in place. Over years, it formed a ridge of sorts like what is shown here.

The trees in the B section are older and more diverse. One is still finding Sugar Maple, but there is also more White Pine, Black Birch, Ash, and, ….

especially along its margin with the ravine, Red Oak. Looks as if the Turkeys have passed this way searching for acorns.

Photo Location C: The Ravine. As far as we can tell, this ravine may never have been completely cleared. Doubtless, wood was cut from it and cattle may have strayed into it. Its Sugar Maple/Hemlock combo is interesting and may reflect a slope with patches of deeper soil and/or selective forestry that favored Sugar Maples (for their sap production).

“Behind our house an old wood road climbs the hill. It goes beside the glen or ravine I spoke about a while ago and it leads through maple woods, hemlock woods, and at last the hill’s open summit which is a birch-thicketed place where the deer are fond of bedding… We have a kind of lookout place, up where the ravine becomes very deep and great oak trees tower in a throng.”

-Alan Devoe, Our Animal Neighbors, p,34

The ravine or gully drops away to our left. Its steep sides are home to both Hemlock (left) and Sugar Maple (right) , together with Black Birch and Shagbark Hickory. These are large, old trees; the slope was too steep to farm, and even logging may have been tricky. The apparent whitewash on the Sugar Maple helps tell you that it is indeed a Sugar Maple – the white comes from a species of crustose lichen found mainly on this tree species.

Those are big, old Sugar Maple. Here, Otter is standing beside one that grows on the west bank of the ravine.

Photo Location D: Coming back out of the ravine we arrived to field D. the southwestern corner of this area had puzzled us in the old aerials, but apparently it is spot which, because it is the steepest part of this field, reverted to forest earlier. Even in the aerials from the 1940s, this corner is invaded by shrubs if not saplings. Its botanical trajectory is a mystery but it is now, in part, a stand of Big Tooth Aspen, an aspen species that tends to favor somewhat drier soils than Trembling (aka Quaking) Aspen.

Admittedly, the Big Tooth Aspen trunks do not stand out in this photograph. The bark of older trees tends to get dark and furrowed, losing the lighter, dusted green that characterizes the bark of many aspen. White Birch is however evident as are the White Pine. All are “early successional trees” and mark this forest as one that came in after the land was opened.

Their bark may not stand out in my photos, but there is no mistaking Big Tooth Aspen’s oval, coarsely toothed leaves, scattered on the ground amongst the Red Oak leaves.

Venturing farther into D, the White Pine are evidently older. The field may have not reverted to forest in abrupt entirety, and these trees may have been the earlier invaders. Note how many of these are multi-trunked. While such trunks would suggest logging in some, stump-sprouting species, these are actually low splits in the trunk rather than multiple stems. Apparently, this might be the damage of White Pine Weevil – a native insects that kills the leaders of open-growing White Pines. When the leader dies, side branches take over the upward growth and, when more than one side branch heads skyward, multiple trunks can result. The abundance of multiple trunked White Pine here suggests that these trees grew up in an open field.

Some parts of the forests of D section, and the adjacent parcels to the north, showed evidence of a reversion to forest from grazing: this is barberry and this ….

is a Multiflora Rose tangle. The presence of such thorny shrubs together with Red Cedar (not shown here) suggest that woody plants initially were entering a field with active grazers. Grazers tend to avoid such spiney fare and so give such plants footholds in the early forest.

This ground shot hints at another fact about this part of the forest: it had wet spots and even patches of standing water. Red Maple leaves are common in this image and, while this species occupies a broad ecological range, it is often found in wooded wetlands.

Photo Location E: What these woods used to look like – open field. These may have been the better soiled or logistically more favorable fields, and so were kept open. In part however their continued openness also reflects ownership patterns – these fields were part of Nat Snare’s Kamefield Farm, an active farm in Devoe’s time. During the rest of our jaunt, we had stayed in the well-storied, little-worked Devoe property.

This field has probably been through cultivation, pasturing and, now at least, haying. We are looking west.

“As I sit facing the open side to the east, I can see a dozen farms and far away to a low lying ridge of wooded hills. It is a panorama of rolling pasture land, dotted with darker green patches that are orchards and checkered by the boundary lines of ancient stone walls. The sunlight lies upon it all, burnishing the shocks of new-cut rye, sweetening the heavy-hanging apples on a thousand trees, distilling the smell of dew-wet meadows.”

-Alan Devoe, Phudd Hill, pp. 75-76.

Walking back west from the field, a look down suggests a new character has entered our play – those deeply incised oak leaves look a lot like the leaves of Scarlet Oak.

We now cross to the west side of the ravine. At this point, the ravine’s creek is a gentle meander out of a small wetland.

Photo Location G: The Phudd Hill erratic (star of a previous blog). Devoe knew of this rock, and, apparently, in his day it was still in an old pasture opening.

“On the summit of a mountain [Phudd], in an open clearing which was once pasture land for sheep, there is a great rock…Generations of farmers have made efforts to blast the rock, but have succeeded only hollowing holes and cavities in it. It is these recesses, some of them more than a yard deep, where the drill went in to make a dynamiting place, which are the homesites of the [Screech] owls. In late April and early May they make their nests, lining the rock cavities with dried grass and soft feathers and bits of straw.”

– Alan Devoe, Down to Earth, pp. 120-121.

Otter looks down from the top of this 15′ high boulder. In the cleft at the picture center is a cavity that may have once held an owl nest.

The forest around the erratic is a thicket of White Pine and, suggestive of past grazing, Red Cedar (the first trunk in from the right-hand margin)

Another hint of a pastured past is this spreading tree along the fence row – it clearly was allowed to grow up in a wide-open situation. One reason farmers allowed such trees to persist was because they provided shade and shelter to the livestock. As pointed out in that earlier blog, this tree might have a lightening scar… one hopes nothing was sheltered below it at the time.

Photo Location H: If you look at the aerial images that lead off this section, the presence of White Pine at point H should come as no surprise. This field did not come back to a uniform stand, rather it is a mix of evergreen and deciduous trees. Perhaps a particular “mother” pine was scattering its seeds over a limited shadow, and other species sent in their colonizers as well. This field was beginning to shrink by 1960, and the White Pines here may date from that period.

This wall may have delimited a pasture, especially if it were topped by wooden rails. Wire fencing is scattered in this forest as well.

The dry soil on this hillside invited in a new forest tree for our walk – those elongate leaves with the rounded teeth are Chestnut Oak. As the scarcity of their leaves suggests, they weren’t the dominant tree of the unpined sections of field H; Red Oak was much more common.

Time waits for no wall or tree. This wall is slowly shrugging to the ground, but it’s also worth noting the evidence of biological decay – the fallen limbs and standing dead saplings. The forest as a whole is not necessarily ailing but one generation – that of the early successional trees which first colonized the open land – is giving way to another kind of forest. That transition involves the death and gradual replacement of the original first comers. If most of these trees germinated at around the same time (likely if the field were suddenly abandoned), then most are now of the same age and will tend to begin senescing somewhat simultaneously.

Photo Location I: The very south end of Phudd Hill – a dry, rocky plateau laced with determined stonewalls. This appears to be the oldest ‘new’ forest of our circuit. It already seems to be at least shrubbed over in our earliest (1948) aerial photograph, although the 1933 map suggests it was more field than forest at that time. This is dry, thin soil with abundant rock outcrops. Despite its relatively long history of reforestation, it was however probably notably more open in Devoe’s time.

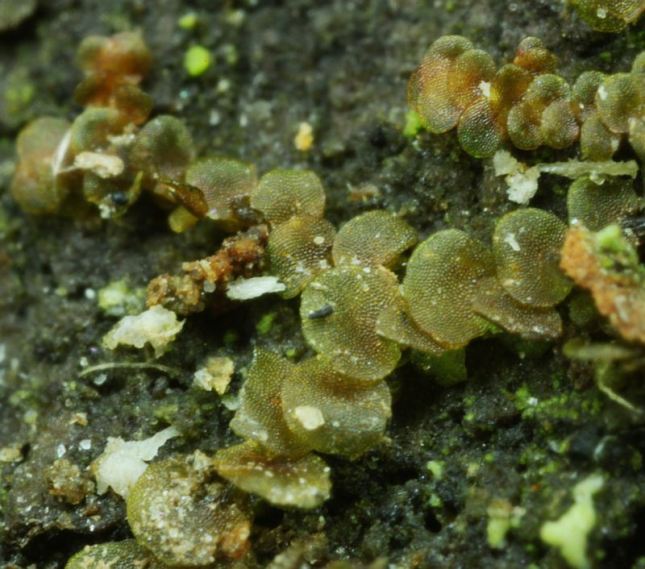

Moss, grass and few trees suggest bedrock near the surface. Perhaps the millenia after glaciation built enough soil to allow for eventual forestation of this spot. However, the subsequent clearing and pasturing (accompanied by erosion, soil compaction and nutrient removal) may have stymied that progress.

“Cottontails make their nests in all sorts of places. Most often, we have found them in our open fields or meadows, frequently in the thin-soiled rocky fields on the slope of the hill…the one that we were able to watch most closely…was on the abrupt slope, overgrown with maple saplings and briers, that rises back of our old house beyond the edge of the garden…I climb this back-of-the-garden hill a good deal just to sit in the hot sun and smell the sun-baked leaves and earth and stare out over the Catskills… Our valley lies winding away below me – old farmhouses and red barns, checkered hayfields and cornlots and rolling pasture, the shining line of the brook as it twists its down the valley with willows along its borders.”

– Alan Devoe and Mary Berry Devoe, Our Animal Neighbors. pp181-182.

The silver snake of creek winding through the distance is still visible from the hilltop, even if the forest is now thicker.

On our way back to the house a few steps takes one across boundaries that mark not only new soils but new histories. We are now looking back at our starting point, the young and Sugar Maplely A field.

And finally, midst the large trees that mark the edge of the steeper ravine, the rising wood smoke of the Devoe/Dufault home.

“I am not a person who likes large views; my preference is for little ones. I am never so much awed by tremendous panoramas of earth and water and sky as I am, for instance, by a luna moth cocoon, jigging and rattling on its walnut twig in the bitter January wind, or by a solitary red-tailed hawk, sailing on rigid wings over the hemlocks behind my house, or by the slow and sinuous progress of a garter snake along the sun-warmed rocks of our old stone wall. That is the kind of view that I like. That is the kind of view I can look at by the hour, and never be tired of. And that, I suppose, is why I live at the bottom of a hill instead of on top of it….”

– Alan Devoe, Down to Earth, p. 139.