Flowers are beautiful. Flowers are also necessary to produce many fruits and vegetables we like to eat. For example, there are no tomatoes without tomato flowers and no cherries without cherry blossoms. Additionally, flowers are a crucial resource for many insects, some of which, in turn, are beneficial for agricultural production.

In this blog, we want to share some late season images (most of them taken in late September/early October 2017) from the Hudson Valley, which illustrate different approaches to enhancing flower abundance on farms. While some of these approaches were the result of deliberate management to invite more flowers and beneficial insects onto the farms, others were more incidental. The photos were taken by various members of our team (see photo credits at the bottom) as part of a multi-farm study to compare the distribution of flowers and insects in vegetable fields and surrounding semi-natural areas. The pictures are from Hawthorne Valley Farm, the Hudson Valley Farm Hub, Ironwood Farm, and Hearty Roots Community Farm.

Hawthorne Valley Farm – Creekhouse Garden

Increased on-farm flowers through adjacent residential landscaping

Our program occupies one of the buildings on the farm, adjacent to a pasture. Since 2010, we have worked slowly, but steadily, to invite more species of native plants into the 1/2 acre yard around the house. The early years of that effort are described on the Hawthorne Valley Farmscape Ecology Program website.

This fall, the rain garden (where we collect the runoff from the parking lot), sported a mix of planted and volunteer native plants, such as New England Aster, Purple-stem Aster, Panicled Aster, Canada and Rough-leaved Goldenrod, Brown-eyed Susan, Obedience Plant, Indian Grass, and Big Bluestem.

View from the rain garden at the Creekhouse towards the barns of Hawthorne Valley Farm (photo by CKV).

The dryer roadside garden has several of the same species (they usually don’t grow as tall, there) in addition to Narrow-leaved Mountain Mint and Wild Bergamot.

A part of the roadside garden at the Creekhouse, featuring (counter-clockwise from bottom left) New England Aster, Narrow-leaved Mountain Mint, Brown-eyed Susan, Wild Bergamot, Big Bluestem, and Purpletop Grass (photo by CKV).

In the shadier areas, Heart-leaved Aster displays a last hurrah of summer with its dense lavender-colored flowers.

A dense patch of Heart-leaved Aster in a shady part of the Creekhouse Garden (photo by CKV).

Much of the former lawn has slowly been transformed into a native wildflower meadow, where New England Aster and Showy Goldenrod put on a spectacular show of colors in late September.

New England Aster and Showy Goldenrod both propagate readily from seeds collected in the fall and stored in a dry cool place over the winter (photo by CKV).

Migrating Monarch butterflies, of which there were a lot more this year as compared to the last few years, were thankful for the nectar!

Monarch on New England Aster (photo by CKV).

But not only the showy butterflies graced the garden with their presence. Honey bees were busily collecting nectar on the different aster and goldenrod species…

A Honey Bee with its pollen baskets filled to the brim, buzzing among the flower heads of New England Aster (photo by CRV).

… as did the native bumblebees.

A Common Eastern Bumblebee is approaching the flower heads of Panicled Aster (photo by CRV).

The less conspicuous small wasps where everywhere. Many of these smaller cousins of the dreaded Yellow Jackets are important beneficial insects for the farmer. Most of them are parasitoids, which lay their eggs into the larvae of other insects and thereby contribute to the biocontrol of pests.

A probably parasitic small wasp (photo by CRV).

Another group of beneficial insects are the hoverflies. Other than bees and wasps, which they often resemble because of their yellow and black markings, these flies do not sting. The larvae of many species are ferocious predators of other insects and also contribute to biocontrol of pests. The adults feed on nectar and pollen, and serve as pollinators. Here are images of three different species of hoverflies found on asters in the Creekhouse Garden.

Most likely, this hoverfly is Syrphus torvus, a common species whose larvae feed on aphids. This adult is visiting the flower heads of Heart-leaved Aster (photo by CRV).

Toxomerus germinatus, another species of hoverfly, visiting the flower heads of Panicled Aster (photo by CRV).

Drone Fly (Eristalis tenax), an introduced, migratory hoverfly, whose larvae are not predatory, visiting the flower heads of Heath Aster (photo by CRV)

However, not all flower visitors were interested in collecting pollen or nectar, or functioning as pollinators. This katydid was happily munching away on the white petals (ray flowers) of a Calico Aster.

A Katydid eating flower parts (photo by CRV).

Another creature was not interested in the flowers per se, but had set up shop to try and catch one of the abundant flower visitors.

A curiously-shaped orb weaver spider, most likely an Arrow-shaped Micrathena (photo by CRV).

Hawthorne Valley Farm – Hedgerows

Increased flowers by letting natural diversity bloom

Hawthorne Valley Farm has an abundance of hedgerows which separate the various pastures and fields. In the Spring, most flowers in this habitat are borne on the native (and non-native) shrubs that compose the backbone of these hedgerows. Late in the season, asters and goldenrods thrive along the unmowed edges of the hedgerows. Such “soft edges” between different habitat types or landscape features might appear ungroomed, but are very important for insect life. Unmowed riparian corridors and infrequently mowed wetlands can serve a similar purpose.

New England Aster of two varieties (purple and pink flowers) grow along the unmowed edge of a hedgerow at Hawthorne Valley Farm (photo by CKV).

Ironwood Farm – Old Fields Surrounding the Intensively Managed Fields

Increased flowers by allowing some former farmland to remain fallow

Ironwood Farm is a young farm reclaiming former farmland. Currently, the intensively managed vegetable fields are surrounded by old fields that have developed into perennial meadows, composed of varying mixes of native and non-native plants. We have observed an exceptional abundance of native bees in the vegetable fields of this farm and suspect that the surrounding old fields and their flowers may help support these bees, which then serve as pollinators in the vegetables. In addition, the Common Milkweed plants (note the large, oval leaves in the center of the image below) in the old field served as food plants for Monarch butterfly caterpillars, making Ironwood Farm a nursery as well as a stop-over for migrating Monarchs.

A goldenrod and aster dominated old field just outside the deer fence of the vegetable field at Ironwood Farm might contribute to the abundance of native bees we observed in the vegetables (photo by CKV).

In the fall, the flowers of New England Aster contrast beautifully with those of Canada Goldenrod in the old field (photo by CKV).

Earlier in the season, the old fields had many flowers of non-native plants, such as Knapweed, which nonetheless were very attractive to native pollinators.

A native bee nectaring on the flower head of a non-native Knapweed (photo by CRV).

Hawthorne Valley Farm – Corner Garden Cropland

Increased flowers through interspersed in-bed annuals

The Corner Garden near the school parking lot is a small, intensively managed vegetable field. The farmers are experimenting with augmenting the abundance of flowers near the vegetables by interplanting annual wildflowers (such as the pink Cosmos pictured below) within the vegetable beds. While some vegetables, such as tomatoes, peppers, eggplants, cucumbers, zucchini, and squash have to flower before producing the vegetable we eat, others, such as lettuce, carrots, parsnips, chard, beets, fennel, kale, broccoli, cabbage, cauliflower, and kohlrabi don’t get to flower before they are harvested. Occasionally, when feasible within the crop rotation, left-over crops (such as the Fennel pictured below) are allowed to bolt and flower, adding to the abundance and variety of flowers in the garden.

Late season flowers in the Corner Garden are provided by a Cosmos plant which was interplanted with Fennel and the Fennel itself, which is allowed to bloom before the bed is seeded with a cover crop for the winter (photo by CKV).

Hawthorne Valley Farm – Corner Garden Borders

Increased flowers through perennial edge plantings

In addition, we have collaborated with the farmers to bring more flowers into the Corner Garden by establishing small plantings of woody and perennial native plants around the perimeter of the vegetable beds. On the right in the image below is an area that was planted in early summer (with the help of several volunteers) with New England Aster, Showy Goldenrod, Wild Bergamot, Narrow-leaved Mountain Mint, Butterfly Milkweed and Swamp Milkweed, all propagated from seeds collected at the Creekhouse Garden, in addition to some Yarrow and Lemon Balm plants. The abundant flowers of New England Aster (patch of purple flowers in image) became a true insect magnet in the fall, feeding migrating Monarch and Painted Lady butterflies, the Honeybees from the nearby hives, a plethora of native bees, hoverflies, and other beneficials, as well as the not-so-beneficial Cabbage White butterflies.

This planting was recently expanded (again with the help of several tireless volunteers) to incorporate a number of additional native wildflowers grown from seeds by volunteer Betsy Goodman-Smith. The perennial patch now also contains Purple Coneflower, Black- and Brown-eyed Susan, Anise Hyssop, Lance-leaved Coreopsis, Mistflower, Cardinalflower, Partridge Pea, Slender Lespedeza, and Purple Prairie Clover (the seeds for most of these species were donated by the Hudson Valley Farm Hub). We are looking forward to this wildflower patch providing nectar and pollen for insects all through the season, next year…

The expanding perennial native wildflower patch in the Corner Garden (photo by CKV).

Hudson Valley Farm Hub – Vegetable Fields

Increased flowers through bed-scale annual insectaries

In the large vegetable fields at the Farm Hub, the farmers experimented with several annual insectary plantings. The image below shows a section of the garden that had been seeded with Prairie Coreopsis in spring and was allowed to flower for a second time to provide late-season floral resources for insects.

An insectary strip of annual Plains Coreopsis integrated in the vegetable fields at the Hudson Valley Farm Hub (photo by CKV).

The Coreopsis insectary became a lunch stop for migrating Monarch butterflies. We estimate that at least 50 Monarchs were nectaring in this patch at a time.

Monarch butterfly on Plains Coreopsis in insectary (photo by DAC).

However, the Monarchs were not the only migratory butterflies who stopped to fuel up on energy-rich nectar. Painted Lady butterflies on their way to Texas and Northern Mexico were even more common than the Monarchs on the Coreopsis flowers.

Painted Lady butterfly on Plains Coreopsis in insectary strip (photo by DAC).

Other visitors to the Coreopsis flowers in the insectary planting included Sulphur butterflies, hover flies, and Honey Bees (all pictured below).

A variety of insects, other than the migratory butterflies, visited the Coreopsis flowers (clockwise from top left): Sulphur butterfly, hover fly (most likely Syrphus torvus), and Honey Bee (photos by DAC).

Hudson Valley Farm Hub – Test Plots

Increased flowers through field-scale planting of perennial native meadows

This spring, we established 4.5 acres of native meadow trial areas in flood-prone fields at the Hudson Valley Farm Hub. We are experimenting with two seed mixes (Mix A and Mix B; see below) to compare their success in establishing meadows without the use of herbicides on former corn fields. We also monitor their suitability for erosion control, soil building, and as insect and wildlife habitat. We received invaluable technical support on this project from the Xerces Society, who is collaborating with the USDA/NRCS throughout the US to help make farms more pollinator-friendly.

Seeding the native meadow seed mix into bare ground in mid May 2017 (photo by CKV).

Mix A is rich in wildflowers and might, eventually, be most attractive to pollinators and other beneficial insects. It is also quite expensive.

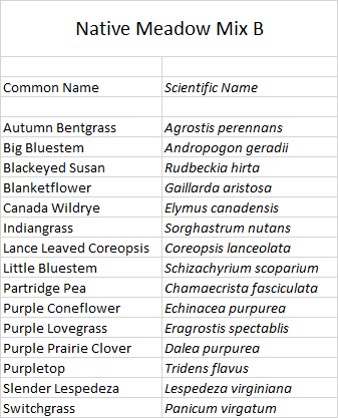

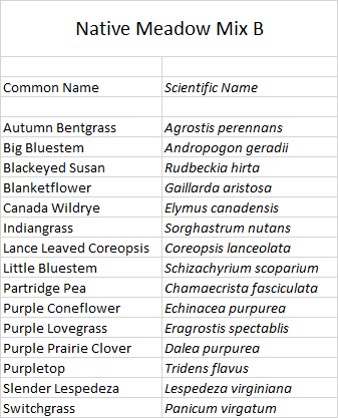

Mix B is rich in native grasses with some wildflowers added. It is more economical and might, eventually, lead to meadows that attract grassland breeding birds as well as a decent amount of beneficial insects.

By early October, some of the test plots are well on their way to dense and diverse native meadows. The vegetation is relatively low because the test plots had been mowed throughout the summer to discourage the annual weeds.

A native meadow test plot (Seed Mix A) in October of its first year (photo by CKV).

A closer look into this patch of meadow (seeded with Seed Mix A) reveals a mix of blossoms from Mistflower (light blue), Black-eyed Susan (yellow), and Blanketflower (red). The seedlings of about 20 additional native plant species are well established and have spent their first season developing a strong root system. They are expected to begin flowering next year. The seeds of a few species remained dormant for the first season and are expected to germinate next spring.

A native meadow established from seed at the end of its first season: the most conspicuous wildflowers are Black-eyed Susan (yellow), Mistflower (light blue), and Blanketflower (red) (photo by CKV).

A closer look at the late season flowers in the native meadow trial (photo by CKV).

Bees, wasps, hover flies, moths, and butterflies, including Monarch and Painted Lady, were visiting the flowers in these meadows, but in smaller numbers compared to the Coreopsis insectary, which had a much higher flower density.

Two very different species of hover flies: Drone Fly on Blanketflower (left) and Helophilus fasciatus on Black-eyed Susan (right) (photos by JM).

The Sulphur butterfly is one of the most ubiquitous butterflies on farms. Its larvae feed on clovers and alfalfa, and adults can be found nectaring on a large variety of flowers.

Sulphur butterfly on Black-eyed Susan (photo by JM).

An exciting observation was the Milbert’s Tortoiseshell butterfly visiting flowers in the native meadow trial. This is a northern species which, in some years, shows up in our region. This is our first sighting of this species in the Hudson Valley in more than a decade.

Milbert’s Tortoiseshell butterfly on Black-eyed Susan (photo by JM).

Hudson Valley Farm Hub – Medicinal Herb Garden

Increased flowers through blossoming herb crops

One of the farmers in training at the Farm Hub chose to experiment with the growing of medicinal herbs, this season. By mid summer, her herb garden was buzzing with bees and hopping with butterflies. The herbs were harvested by the time we took our last round of photos, so here are a couple of images from the herb garden in July.

The medicinal herb garden in July. In full bloom at this time were Toothache Plant (yellow), Calendula (orange), and Blue Vervain (purple) (photo by CKV).

It was particularly impressive, to see the Blue Vervain, a native plant of wet meadows, in a dense bed of obviously very happy plants in full bloom. The insects were all over them in July!

Blue Vervain in the medicinal plant garden (photo by CKV).

Hearty Roots Community Farm – U-Pick Flower Beds

Increased flowers through bee- and butterfly-friendly cut-flower beds

Another type of flower found on several farms this fall were ornamental plants grown for cut flowers. While ornamental flowers often originate from other parts of the world (e.g., Calendula comes from Southern Europe and Strawflower from Australia) and horticultural varieties bred to please the human eye often don’t provide much (if any) nectar and/or pollen for insects, we were happy to observe during our flower watches in the cut-flower beds of Hearty Roots Community Farm, that some species were very popular with the insects.

One of them was Zinnia, an easily grown annual which is represented in many flower gardens and a staple in cut flower arrangements. It is native to the Southwestern US and into South America.

A bed of Zinnia in the cut flower garden at Hearty Roots Community Farm (photo by CKV).

The Monarchs and Painted Ladies might “know” this plant from Mexico and seem to LOVE it! (Of course, the individual butterflies we observed here this fall have not yet been in Mexico, so their “knowledge” of Zinnia–if any–would be at the level of the species which have co-evolved with the nectar plants.)

Monarch butterfly on Zinnia (photo by DAC).

Painted Lady butterfly on Zinnia (photo by DAC).

Globe Amaranth is also often a component of locally grown flower bouquets, but its natural distribution is even more tropical than that of Zinnia, from Central into South America. Its flower heads are reminiscent of clover and seem to be very attractive to a variety of butterflies.

A bed of Globe Amaranth in the ornamental flower garden at Hearty Roots Community Farm (photo by CKV).

It was visited by some butterflies that are common resident species of our area farms, such as the Sulphur and Gray Hairstreak.

Sulphur butterfly on Globe Amaranth (photo by DAC).

Gray Hairstreak butterfly on Globe Amaranth (photo by DAC).

However, we also observed several butterfly species on the Globe Amaranth, which are resident in the southern US and only sometimes stray as far north as our region. These include the Fiery Skipper, Common Checkered Skipper, and Common Buckeye.

Fiery Skipper butterfly on Globe Amaranth (photo by DAC).

Checkered Skipper on Globe Amaranth (photo by CRV).

Buckeye butterfly on Globe Amaranth (photo by DAC).

Fortunately, there are many possibilities to enhance flower abundance and insect life on farms (and in your gardens!), whether it involves adjusting the mowing schedule of natural areas/field edges/surrounding old fields so that the wildflowers can blossom; allowing certain vegetables to bolt and bloom; planting flowering medicinal herbs or pollinator-friendly cut flowers; interplanting annual flowers with vegetables, either as individual plants, or in insectary strips; using flowering cover crops; or establishing perennial wildflower areas at the field or nook & cranny scale. Each of these approaches can help make the farmscape more diverse and alive. They vary in their scale and in the time and money investment they require, so think about what’s the best fit for your situation. Where there are suitable flowers, the pollinators and other beneficial insects will be rewarding you with their beauty and service.

We thank the farmers at Hawthorne Valley Farm and the Hudson Valley Farm Hub for their collaboration with the experimental establishment of native wildflowers. We also thank them, and the farmers at Hearty Roots Community Farm and Ironwood Farm for tolerating our research for the multi-farm comparison of the distribution of insects across on-farm habitats.

Photo credits: Dylan Cipkowski (DAC), Julia Meyer (JM), Conrad Vispo (CRV), and Claudia Knab-Vispo (CKV).